Pendleton Woolen Mills was founded in Oregon in 1863 by a British weaver, Thomas Kay. They’re most famous for their wool blankets, including Native American trade blankets, and their wool shirts. I used to sell the shirts and blankets when I worked in a men’s retail store. Inside every shirt was stitched a label, on a blue background in yellow letters: WARRANTED TO BE A PENDLETON. The wording always struck me. Warranted.

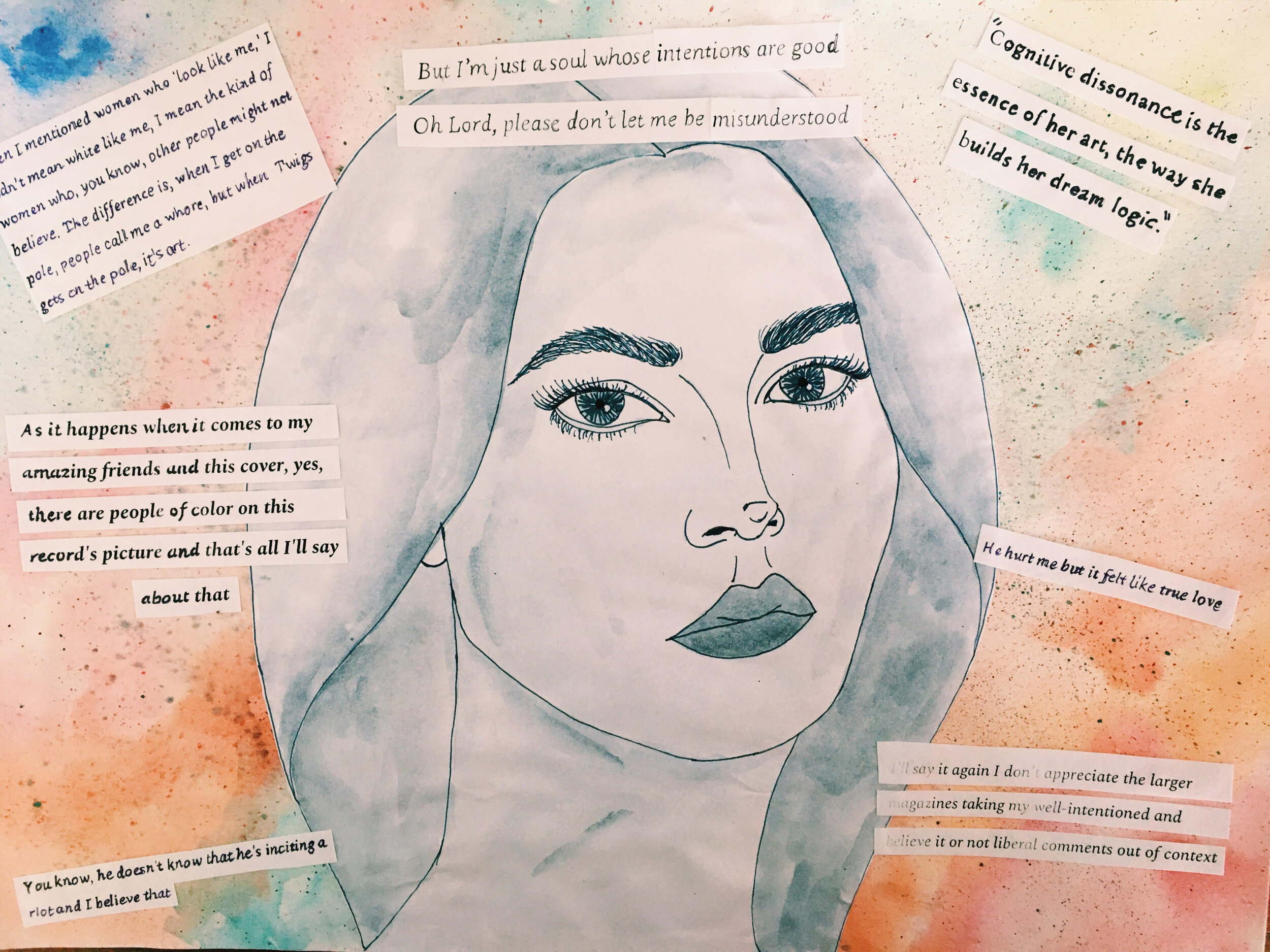

I don’t really understand copyright law, so I hope this painting (by me) of the Pendleton label does not result in any phone calls from their lawyers.

It’s the past tense of the word warrant, which is itself a version of the word warranty. The word warranty comes from the Old French guarantie, which means that, yes, it’s cognate with our modern English word guarantee. It first referred to a covenant made in real estate transactions binding the grantor of an estate and the grantor's heirs to warrant and defend the title and the estate itself. Nowadays it’s morphed into a promise a manufacturer makes to repair or replace a product within a certain time frame. The ironic thing is that Pendleton doesn’t have that kind of warranty attached to the shirt itself--the company website cheerfully explains that “‘Warranted to be a Pendleton’ is our quality credo pertaining to the product, the people and the personality that make our company unique. It's a vital part of our family legacy, as honored today as it has been since 1863.” If one of the seams needs mending or you need more replacement buttons, you can’t send the shirt in somewhere for repair. The warranty label is simply a pledge that this shirt is a Pendleton.

In other words, the warranty is a mark of authenticity. Warranted to be a Pendleton means it’s the real thing, made of US-sourced and US-woven virgin wool (although it’s often cut and stitched together in another country). It means you’re getting the high quality garment you paid for. And people love Pendleton. To my dad, the word Pendleton refers to the entire product category of mens plaid flannel shirts (such as, “should I bring a Pendleton?”). He won’t wear any other kind. When I sold these products in store, people would point to the Pendleon label and talk proudly about the wool blanket that had been in their family for eighty years. I saw countless customers run their fingers over the front of a shirt and pause for a second, realizing that it actually was made of real wool. The brand really means something to people.

All of this makes me think about the concept of authenticity.

Authenticity is a buzzword, which at the very least renders its meaning bifurcated. There’s what it really means, and what people want it to mean. Corporate leaders talk about authenticity as a way to make themselves seem…less corporate. Music blogs are obsessed with it as a metric of an artist’s merit. Instagram influencers, who happen to be predominantly women, are held suspect for their apparent lack of authenticity. But what is authenticity really about? If we use the Pendleton shirt and its label as an example, it refers to a deep kind of integrity. The Pendleton shirt cannot be anything other than what it is; you can button it all the way up and tuck into some nice pants, but you’re still going to look like a lumberjack or a ranch-hand, at least a little bit. The Pendleton shirt has no pretense, it puts on no airs. You’ll never confuse it with some logo-festooned shirt from Gucci. Nor will you confuse it with one of its cheaper imitators; the fabric is too sturdy, the design details are too distinctive, the colorways are too classically masculine and understated. It smells too much like wool to ever be confused for a polyester blend. You can wear it most places, but not everywhere--not in a heatwave, not to a wedding, not to a christening, probably not to court. It remains indelibly marked by its own origins and history, so much so that for many people it more or less symbolizes the American West, and all the miners, loggers, and fishermen who settled there. Its symbolism has evolved over time--it’s now heavily associated with surfer culture, too--but its essential qualities have remained the same. In other words, it’s true to itself.

But I don’t really think that this kind of authenticity is what the corporate fucks are talking about. Or even what we are talking about half the time. Authenticity in the corporate world and in the culture more broadly, seems to have been conflated with uniqueness. Being ‘authentic’ means having several unique qualities and unique achievements. This is why people like craft beer so much, because you can get distinctive, weird beers that stand out from the plain, mass market stuff at the liquor store. (Whether or not a mango milkshake hazy IPA should exist is another question). My own generation, the relentlessly pilloried millennials, apparently care a lot about authenticity, judging by our penchant for artisan sourdough, craft cocktail ‘experiences’, boutique coffee roasters, and so on. Think of the maligned “basic bitch” stereotype--a woman who likes basic things like Starbucks, Top 40 music, and shopping at Target is an object of ridicule. It’s embarrassing to admit you like pumpkin spice lattes or Katy Perry or lululemon yoga pants. You must not be trying hard enough to be authentic. To be different. How humiliating to like the same things that other people do.

It’s not enough to buy the right kind of artisanal oat milk matcha latte, the right kind of one-of-a-kind typography print for your wall. It’s not enough to participate in the economy of “authentic” brands and products. You have to show people all the time how authentic you are, by showing yourself experiencing these authentic experiences and being authentic as a person. You have to post about the latte on Instagram. Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn, Clubhouse—they’re all there to telecast your uniqueness on the regular (side note: what the fuck is Clubhouse). Even your job is supposed to be an arena where you can show off your unique, singular qualities and skills. But all of this social pressure to “be authentic” carries an inherent contradiction. Sociology professor Joseph E Davis writes, “in order for people to distinguish themselves, they must seek attention and visibility, and positively affect others with their self-representations, personal characteristics and quality of life. In doing so, they have to take great care that their performance isn’t perceived as staged. To be ‘authentic’ – genuine – they have to give the impression that they’re just being themselves.” If they show the effort involved in this performance, it ruins the whole effect. Authenticity must be uniqueness, broadcast to the world. It must appear to take no effort at all, and yet it must be performed.

Now, for people who are born performers, this is perhaps not such a problem. Mariah Carey would still be the way she is even if she had become a nail technician, a receptionist, or a lawyer. But for the rest of us, it’s kind of crazy-making. This is because much of the work of being authentic--of being true to yourself, and having integrity--happens on the interior, in private. We behave authentically when we decide whether or not the caprices of a certain job will come into conflict with our own moral code. We behave authentically when we engage in deep questions of faith, doubt, love, and trust. When we make choices that align with our beliefs and principles. And for a lot of us, behaving authentically--I mean really authentically--would include disqualifying ourselves from at least one component of the rat race.

Our “true” selves are often at odds with society. An example of this is the story of St Francis. He was born wealthy, but he gave it all away, including the clothes on his back, to follow God. He committed to a life of poverty, chastity, obedience, and public service. That’s an extreme example, but it’s helpful because it illustrates my claim that the “true” self doesn’t always conform to societal standards of excellence. You know, St Francis’ parents thought he was a fucking nut. But what mattered to him more than anything was serving God, so he was happy to be labeled a fool. A friend of mine decided he wanted to be an outdoor photographer. In order for him to take this path, he lived on a bicycle and slept in a tent for two years. Eventually he upgraded to a van. It took a long time for him to get any paid work, and he made many sacrifices. And yet, he basically has no regrets. He has something I envy: he has peace of mind. And when he does share about his life on the internet, it doesn’t come across like he’s got anything to prove. He’s just telling you a story about his life, about what it took to get the shot of that particular wave. In other words, he would still be doing this job even if there weren’t people on Instagram to show it to.

Paradoxically, it’s hard to be authentic to yourself when there’s always pressure to perform. When it feels like you aren’t meeting the cultural standards of success, it’s easy to feel isolated. I think for a lot of us, a more authentic life would include deeper ties to our families, relationships, and communities. It might involve greater social cohesion, more involvement with political or social movements. But the expectations of authenticity are mostly centered on the individual and that individuals’ differentiation from the collective. In an already highly individualistic society like America, this is a recipe for further alienation from each other. It’s no wonder so many of us are pathologically lonely, and were that way even before the pandemic made it worse. We don’t need to impress each other with our differences as much as we need to connect with each other. And I just don’t think that can happen effectively if we’re performing all the time.

The performative quality of ‘authenticity’ has also contributed to the rise of social media activism. By this I mean the very surface-level sharing of infographics and hashtags associated with certain movements, without doing the actual work of joining the movement. This is a pretty screwed up dynamic because people prioritize public-facing signals of solidarity over doing the work. Sometimes activism means doing work that is difficult, and that no one will see. Sometimes it is also more honorable to do the work without drawing attention to it, even if you could. But we seem to be prioritizing more public-facing kinds of activism. We need to show everyone the receipts. The emphasis on sharing everything you’re doing to combat a societal problem also ends up putting the focus on you. And that doesn’t sit right with me. It also seems to result in less effective, you know, activism. If you care about homelessness, the thing to do is to donate to a homeless shelter, or write to your city council about it. But if you don’t post about doing these things, people might think you don’t care about homelessness. And of course it’s important to be vocal about issues we care about, and to engage in both public and private discussions about them—my point is that the work shouldn’t stop there.

The Pendleton label—the one with the warranty—goes on the inside of the shirt. The idea is that you don’t need to broadcast the logo because people already know just by looking at it, that it’s a Pendleton. The label is there to assuage any doubts. I would like to be that way—more concerned with going about my day to day life in a way that feels true to me, than constantly checking to see if other people are also seeing how authentic I am.

Because people in real life, in real interactions outside social media--they can usually tell if you’re putting on an act. Not just with activism, but with everything. You can’t keep up the charade forever. Our performances are creating more distance between each other, rather than actually fostering connection. We must work harder at introspection, not performance. That way our outside behaviors and our inside beliefs will match up so well that we are warranted to be our real selves.

I mean, I know none of this is news to anyone that’s been paying attention. But I know that I need to be reminded of it all the time.